In the fall of my senior year, I took an undergraduate course at MIT in digital systems and computer hardware design. The class is known to students in these parts as 6.2050 ("six two oh five oh") or among friends just as "two oh five". The class focuses on digital systems design in SystemVerilog, a hardware description language used in the industry to design and verify digital circuits. Throughout the class, we used Xilinx ("zy-links") Spartan 7 field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) in order to test our designs. In lab, we've designed circuits to process 8-bit audio, generate HDMI video signals, and perform real-time image processing.

For our final project, my friend David proposed to me an RSA cryptographic hardware accelerator. This device would connect to a personal computer to conduct real-time, asymmetric encryption. We decided on this because asymmetric encryption in real time is very difficult due to its computationally intensive nature. By creating specialized computer hardware capable of performing encryption and decryption in real time, we believe our approach has a strong advantage over software-based solutions. For our encryption algorithm, we selected RSA, a common asymmetric-key cryptosystem that would be relatively easy to implement in hardware.

Because we created a piece of hardware that can "lock" and "unlock" secure messages, we decided to refer to our project as an "RSA keychain". We began work on the project in late October and concluded in mid-December.

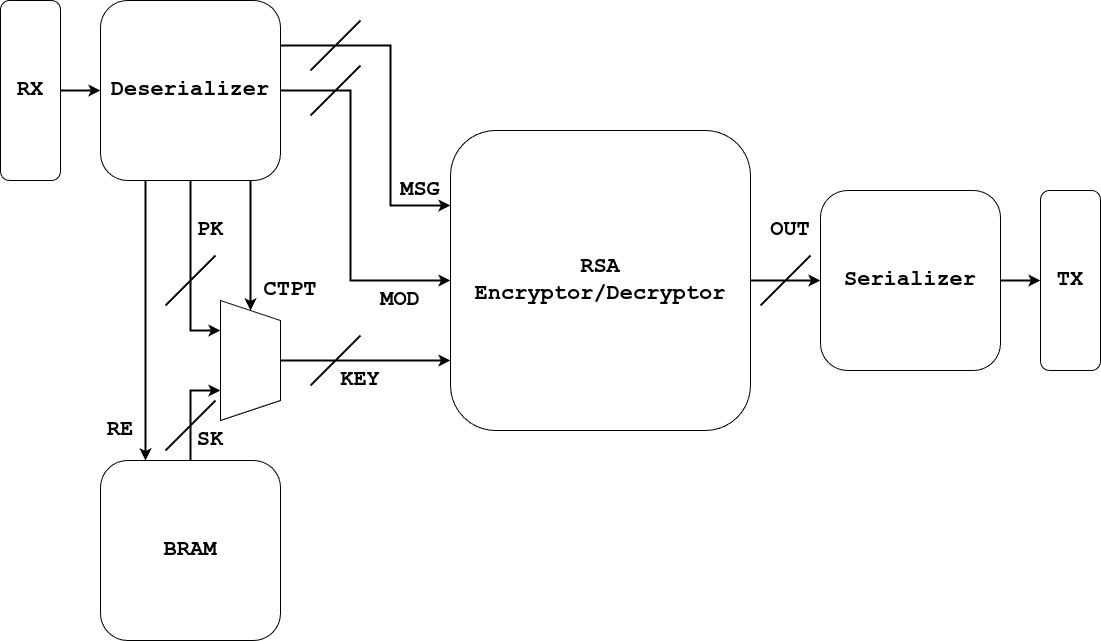

The below block diagram represents a high-level overview of our project. We plan to make the key and message sizes parametric, so we can change them throughout the design process without affecting the overall system architecture. The bulk of the work will be performed by the encryption/decryption block, which will perform the calculations necessary to encrypt and decrypt messages using the RSA algorithm.

An important note is that the RSA secret key is stored on the keychain hardware and is not accessible to the device to which it is connected. We intentionally designed the keychain in this manner to maximize the security surrounding the secret key and minimize the chance it can be accessed by means of hardware vulnerabilities.

The implementation process was highly intensive and required significant verification at every step of the way. The most significant hardware module contained in our design was the encryption/decryption block, which had to evaluate expressions of the form \( x^y \, \mathrm{mod} \, z \). These expressions are the core of the RSA cryptosystem, so we spent the majority of our time on the implementation and verification of this hardware module. We performed simulation using Cocotb, a Python-based testbench environment, which allowed us to automatically generate random inputs, simulate the performance of the hardware module, and check if the results of the hardware calculation matched the intended output.

We experienced a number of challenges while working on this project. However, the most significant difficulties were related to the synthesis process as well as timing requirements.

Though Cocotb simulations verified our design for key sizes up to 512 bits, we were unable to synthesize designs with key sizes larger that 32 bits. We are unsure exactly what caused this issue... we used Xilinx Vivado to conduct synthesis, placement, and routing, and the software tool would repeatedly freeze before it could complete the synthesis operation. After conversation with a course TA, we found ourselves unable to debug the Vivado issue and we focused on ensuring our design worked in Cocotb simulations.

We also ran into significant issues with meeting setup requirements. This was due to the large integer arithmetic operations required by the RSA encryptor/decryptor hardware module. We were in fact able to pinpoint that our critical path was occurring in a hardware subtraction of two large integers. In the interest of simplicity, we opted to lower our clock speed from 100 MHz to 10 MHz to meet timing requirements. However, in the future, a commercially viable version of our product would use more complex pipelined arithmetic logic hardware, which would allow clock speeds (and throughput) to remain as high as possible.

Thanks to my project partner and my friend, David Choi, for originally conceiving of this idea and for all of his contributions to the project. This project could not exist without his hard work and dedication.